About ground-hornbills

The Southern Ground-hornbill (Buvorcus leadbeateri), “SGH” from here on, is endemic to Africa and has been recorded in 16 African countries, these are: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, Malawi, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Ground-hornbills are resident, occurring from sea-level to altitudes of 3000 metres on fixed, firmly defended territories that range in size between 100 – 250 km ² in savanna, grassland and open woodland. Open habitats with a short grass layer are ideal for foraging within these areas.

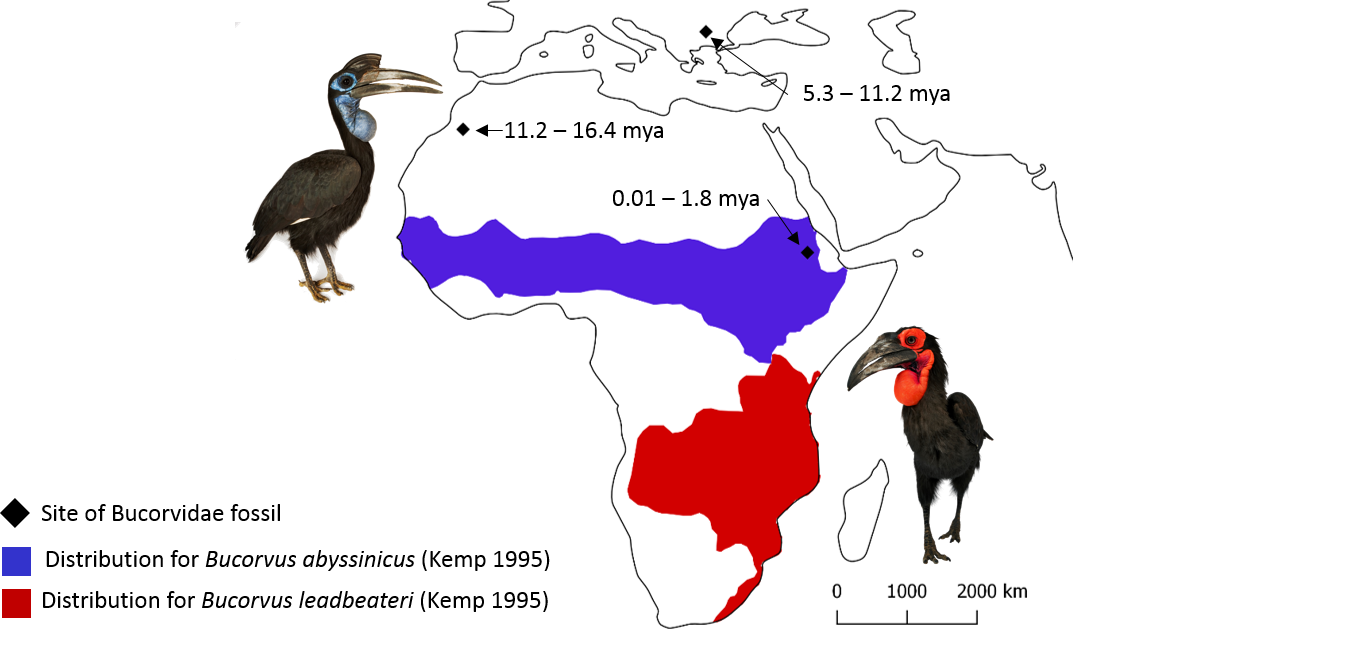

SGHs are mostly found south of the equator but have a small overlap in distribution with the Northern (Abyssinian) Ground-hornbill (B. abyssinicus), the other member in the genus Bucorvus and family Bucervidae, which occurs strictly north of the equator. This overlap occurs in Uganda and Kenya and is credited to dispersals, rather than breeding individuals. Bucorvus abyssinicus is mostly found in dry savannas, whereas B. leadbeateri is found in the moister subtropical and tropical savannas.

The SGH has disappeared from several parts of its former range up to as much as 70% in South Africa and from extensive areas in Zimbabwe and Namibia. In South Africa, the core concentrations are in the extensive conservation areas of the Kruger National Park (KNP) and adjacent private reserves; the conservation and farming areas of northern and midland KwaZulu-Natal and the rural areas of the Eastern Cape. SGHs occurred historically at low densities in Swaziland and a gap in the range is becoming apparent, separating the populations in northern KwaZulu-Natal and the southern KNP. In South Africa, SGHs are found mostly in savanna or grassland habitat.

Micro-scale distributions of Southern Ground-hornbills are often found around drainage lines and around waterholes. Large drainage lines are in fact believed to act as corridor-links for some populations in Zimbabwe and northern Limpopo Province of South Africa, where groups are encountered along the Mogalakwena, Limpopo and historically, the Olifants Rivers. They are attracted to these areas, not because they need water, but rather as a result of the richer prey diversity and the availability of larger trees along the riparian zone for roosting and nesting.

The Southern and Abyssinian Ground-hornbills are the only two species in the genus Bucorvus, classified under the order Bucerotiformes in the family Bucorvidae, a unique sister clade which diverges from the Bucerotidae or nest-sealing hornbills. The Bucerotiformes originated in Africa and following phylogenetic divergence, spread out and eastward to South Asia, South-East Asia, and marginally Australasia to evolve further. Some members of Tockus, and Buvorcus families on the other hand, remained in Africa. Tectonic and climatic changes then proceeded to split up the ranges on both the African and European landscapes even further.

Mitochondrial molecular and nuclear data is the basis that separates the clades into different families as well as significant morphological and behavioural differences. Buvorcus syncervical vertebrae (vertebrae between the head and the body) fossils have been found that pre-date those of Bucerotidae. In Buvorcus, the atlas and axis bones in the cervical vertebrae are fused together. This suggests that the first ground-hornbills were already unique in the primitive years from the nest-sealing family, with the back of the neck designed for strong head movements when supressing and foraging for live prey . This contrasts with the Bucerotidae where the design of these bones are designed for carrying a heavy casque since these types have a frugivorous or omnivorous diet.

It is thought that for the first Bucorvus ancestor to survive in Africa where savannas and grasslands were expanding, it had to adapt to a carnivorous diet in order to sustain its large body and its energy requirements. The loss of nest-sealing behaviour (practised by other hornbill species) has been attributed to several possible theories including predation risk to the female and in-nest heat sensitivity.

To highlight the distinctiveness of ground-hornbills further, they possess 15 cervical vertebrae, whereas all other hornbills have 14. They are also the most terrestrially adapted with long legs and a shorter tail, and they walk only on the terminal joints of their short toes, which allows them to walk fluidly whereas many other hornbill species hop.

Bucorvus means ‘large crow-like’ bird and leadbeateri comes from Benjamin Leadbeater (1760-1837), a Victorian naturalist from London who first described the type specimen.

Ground-hornbills are entirely faunivorous, feeding actively on a wide range of arthropods (insects and arachnids), reptiles (snakes, lizards and tortoises), amphibians (frogs), small birds and small mammals up to the size of a hares. The Southern Ground-hornbill will also scavenge opportunistically on carrion and on the odd occasion, will feed on fruit and seeds. They have even been observed picking ectoparasites from the hides of African warthogs.

Groups usually remain within a 3 km radius of the nest when breeding, and travel up to 6–8 km per day to and from the nest. During winter, groups utilise the full extent of their 100 – 250km² home range, but significantly reduce their daily foraging movements.

A large database of over 2000 records on foraging observations indicates that SGHs obtain essentially all their food from the ground. Despite being strong fliers, due to their foraging strategy, groups spend on average 70% of their day walking in open areas, searching for live prey by scanning the ground closely using their sharp vision or by digging with their strong beaks (an action they readily perform in the dry season, when surface prey is scarce). If food is plentiful, they will spend less time walking and more time resting or playing.

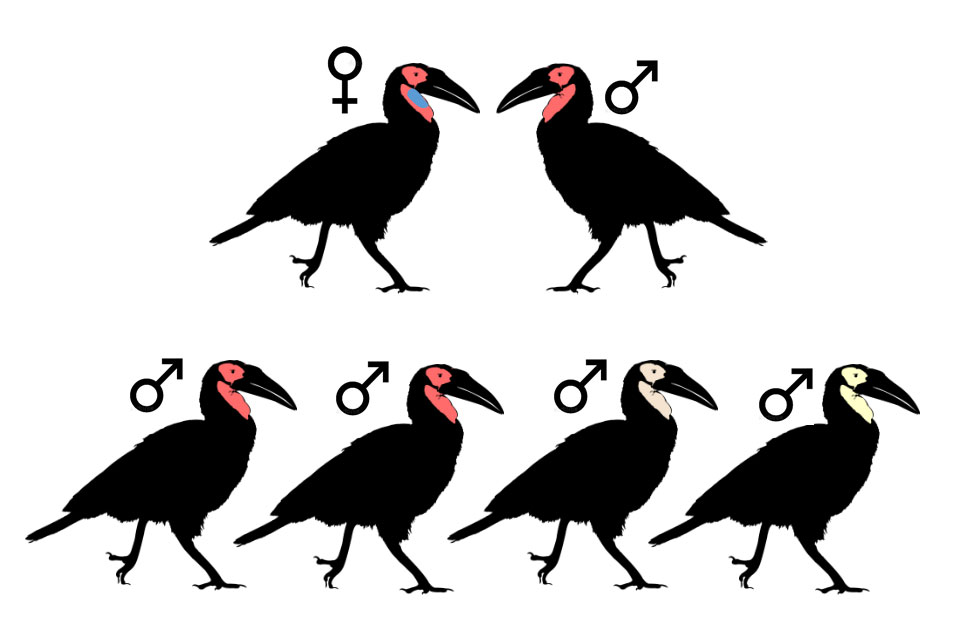

Southern ground-hornbills are the largest known cooperative breeding bird species in the world, with groups consisting of one dominant male and female that monopolize all reproduction, and non-breeding helpers, mostly in the form of previous sons that delay dispersal from their natal territory to help care for future chicks, since the raising of young is demanding in this species. Copulation is strictly between the alpha pair, and only one adult female is tolerated in a group.

The one trait that SGHs have in common with other hornbill species is that they nest in sizeable, natural cavities, situated high in large trees, rock faces or earth banks. They are unique in that the female does not seal herself into the nest and does not shed her feathers. Due to their larger size and their strong pecking ability, they are, to a degree, able to excavate and make cavity modifications, but are largely reliant on an already existing cavity. Once a group has found a nest, they will reuse it for years to come and centre their territory around it. The female incubates her eggs for 42 days and will brood her hatchling for a further 30 days, being confined to the nest during this period, leaving only periodically to defecate and preen herself which is for a short time.

The other members of the group, especially the alpha and beta males, take part in the breeding process by caring for the female before, during and after the nesting period by feeding her and then the chick when it hatches. In the months building up to the breeding season, the males, especially the alpha male, will start making preparations by bringing leaf material to line the nest and the female will begin sitting in it for longer periods. The males will begin feeding her more during this time. Copulation occurs frequently between the dominant pair, and eggs are usually laid after the first good rains and arrival of food abundance.

A critical aspect of Southern Ground-hornbill biology, is their slow breeding rate together with their low chick recruitment. They breed only once during the wet season in the summer from September to December. Several years can occur between breeding and the overall fledgling rate is one chick per group every nine years. In 80 % of clutches, the female lays two eggs, three to five days apart. This results in the chicks hatching at different ages and results in the older chick outcompeting the younger sibling on most occasions. The younger chick is simply ignored by the adults and succumbs to dehydration within a number of days. This has been hypothesised as an insurance policy that the second chick is simply there in case the first does not survive. Otherwise, ground-hornbills will not rear the second chick, even when food supply is steady.

Loss of suitable habitat and nesting sites

Seventy percent of open savannas and grasslands which are a SGH’s preferred habitat have been transformed due to human expansion, over-grazing and climate change and a large portion of the population occurs in fragmented patches of suitable habitat. Only 20 % of this is formally protected. Overgrazing and increased carbon dioxide levels has resulted in extensive bush encroachment. One significant limiting factor for ground-hornbills, is the decline of large nesting trees, which are being removed from the landscape mostly by humans and elephants and to a lesser extent flooding or fire (Mograbi et al. in press). The lack of a nest site results in a long delay in reproduction and reduced stability of groups.

Seventy percent of open savannas and grasslands which are a SGH’s preferred habitat have been transformed due to human expansion, over-grazing and climate change and a large portion of the population occurs in fragmented patches of suitable habitat. Only 20 % of this is formally protected. Overgrazing and increased carbon dioxide levels has resulted in extensive bush encroachment. One significant limiting factor for ground-hornbills, is the decline of large nesting trees, which are being removed from the landscape mostly by humans and elephants and to a lesser extent flooding or fire (Mograbi et al. in press). The lack of a nest site results in a long delay in reproduction and reduced stability of groups.

Secondary Poisoning

Southern Ground-hornbills are susceptible to secondary poisoning. Whole groups can be killed when they scavenge off carcasses deliberately laced with poison to target other carnivore species. Lead toxicosis is another poisoning problem for the species. When game animals are shot with lead bullets during hunting excursions, the lead fragments disperse throughout the carcass, and remain in the tissue and the offal that is discarded. The ingestion of this offal by Ground-hornbill groups can result in fatalities.

Southern Ground-hornbills are susceptible to secondary poisoning. Whole groups can be killed when they scavenge off carcasses deliberately laced with poison to target other carnivore species. Lead toxicosis is another poisoning problem for the species. When game animals are shot with lead bullets during hunting excursions, the lead fragments disperse throughout the carcass, and remain in the tissue and the offal that is discarded. The ingestion of this offal by Ground-hornbill groups can result in fatalities.

Wide spread declines are also attributed to control projects in range states where poison or pesticides are used to kill off large colonies of the crop-raiding bird species, Red-Billed Quelea Quelea quelea. Southern Ground-hornbills are one of the non-targeted predatory species that is affected negatively when they consume intoxicated Quelea carcasses.

Direct persecution

Window-breaking: Their territorial behaviour, which involves active conflicts with any invading group of ground-hornbills on their territory, results in them breaking any reflective and shiny objects such as mirrors, windows, and vehicle bodies that they come across. This is because to them, they are fighting an intruder when they see their reflection. This can result in significant damage to people’s property which often results in their persecution.

Window-breaking: Their territorial behaviour, which involves active conflicts with any invading group of ground-hornbills on their territory, results in them breaking any reflective and shiny objects such as mirrors, windows, and vehicle bodies that they come across. This is because to them, they are fighting an intruder when they see their reflection. This can result in significant damage to people’s property which often results in their persecution.

Traditional medicine: SGHs are occasionally, opportunistically hunted and killed for the muthi trade, particularly in years of drought, due to their strong cultural importance as the "rainbird". In some instances, only a single feather is required for a rain ceremony, which is thought to be so powerful that if left in the river for too long flooding will result.

Road-kill: Since ground-hornbills are attracted to mowed lawns and open areas, they often walk and forage along roads and are therefore as risk of being hit by passing vehicles.